El Sobrante Press ESP

Hiking in the USA - Page 1

Contents

A. Hiking the Yosemite Backcountry (Parts I and II)

B. Half Dome--Reaching the Summit

C. Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah

D. Zion National Park, Utah

A. Hiking the Yosemite Backcountry (Part I)

In my first year of living in California I paid a couple of visits to the back country of Yosemite National Park. It all started when a runner friend in Maryland asked if I’d be willing join her in a multi-day hike into the wilderness along the John Muir Trail. Backpacking was new to me, but I was eager to give it a try. To avoid the usual Yosemite crowds, we settled on a date in early-September when most vacations were ending, and students were back to school. I submitted a request to the National Park Service and got a permit for a 6-day wilderness hike on September 4-9, 1996.

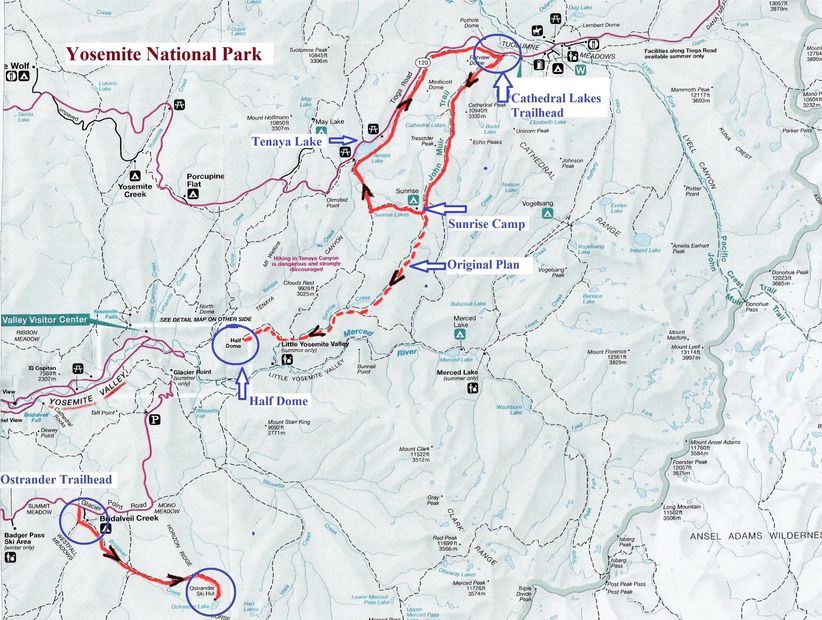

After much discussion with experienced hikers at work, the plan was to enter the wilderness boundary at the 8,200 ft Cathedral Lakes Trailhead off Cal Rt 120, northeast of the Yosemite Valley. From there we’d follow the John Muir Trail southwest over hill and dale, mountain and valley, down to the iconic 8,800 ft granite Half Dome monolith. We’d climb Half Dome and afterwards spend the night outside the wilderness at a nearby campground. On day 7 we’d hike into the Yosemite Valley and complete our adventure with a shuttle bus ride back to our original trailhead. A 4-hour car ride and we’d be back to my home in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Having none of the proper equipment needed for such an adventure, I’m sure I spent well over $1,000 on the camping gear: large size, heavy-duty backpack, 3-person tent for extra space, a ground cloth, sleeping bag, lightweight cooking and eating utensils, water purifier pump, hiking shoes, sleeping bag, stove and fuel, topographical maps, first aid kit, flashlight, sandals, backpacker’s trowel, etc. Since we’d be carrying everything on our backs for several miles every day, it was essential that everything be as light as possible but durable and easy to assemble.

A Field Test

Two months prior to the planned September hike, I was invited to join several of my work colleagues on a Yosemite backcountry expedition for a long holiday weekend beginning on Thursday, July 4th. This provided an excellent opportunity to test my stamina and check out the new equipment in actual field conditions.

This backcountry excursion began south of Yosemite Valley at the Ostrander Trailhead off Glacier Point Rd. After assembling our gear and donning our packs, we headed into the wilderness on a 6-mile hike to our campsite near the ski hut at Ostrander Lake. The ski hut was built for use by cross-country skiers in 1941 by the Civilian Conservation Corps. It’s not open in the summer months. Our hike through the forest took us from 7,000 ft to the mountain lake at 8,600 ft.

JB on the hike to Ostrander Lake

The hike to the lake proved instructive in terms of how to organize the large backpack to provide access to gear and food, particularly what items could be hung on the outside and which were best stored in the pouches. The boots got their first workout and proved kind to my feet. Once the camp set-up was complete some of us hiked the local area, including the lake and high ground, checking out the scenery and wildlife. Now and again, we encountered other hikers or campsites, but these were sparse.

An exploratory hike

The weather was kind to us, no rain, mostly sunshine and temperatures in the 80s. Although I didn’t partake of it myself, there was plenty of hard liquor brought along to ease the transition from city life to wilderness camping. On one occasion I volunteered for an ice retrieval expedition—climbing up a nearby summit to fill a backpack with snow, making cool drinks a real possibility. Even though the calendar indicated early July, snow and ice was still prominent in the shadows at the upper levels.

Surrounding peaks

There were lots of opportunities for exploratory hikes around the lake and into the high mountains

Part of the hiking contingent

Camping at the lake

Ostrander ski hut

At the end of our stay, we packed up our gear, cleaned the area of any trace of human habitation and headed back to the hustle and bustle of civilization.

Returning to civilization

Along our return path, the lead person in the group came to an abrupt halt, he turned and held a finder to his lips with a “Shhhh.” There about 20 yards off the path to our left was the biggest deer I had ever see—a large buck with a full head of antlers. After a few seconds, the deer turned back into the forest and we continued on our way. A respectful confrontation of man and beast.

A. Hiking the Yosemite Backcountry (Part II)

Yosemite National Park Map (Courtesy of National Park Service)

September in the Wilderness

It wasn’t long after the Ostrander hike that I got some bad news from back east. Joanne, my would-be Maryland hiking partner, had broken her ankle and would be in a cast for 8 weeks. The early September Yosemite hike was in jeopardy. Luckily, I was able to get a 2-week extension on the backcountry permit. Our hike was now scheduled for September 18-23. We assumed her ankle would be healed and the fall weather would be kind to us.

On Wednesday, September 18 we arrived at Yosemite’s Tuolumne Meadows Cathedral Lakes Trailhead and began our early afternoon excursion along the John Muir Trail into the wilderness. The trail had been getting so much use over time that it was severely rutted in places to a depth of 6-8 inches. The erosion probably took years to develop. A slow 3.5-mile hike got us to our first night’s stop at a rough campsite near the Cathedral Lakes. I carried the tent, cooking utensils, and a 15” bear canister, plus each of us carried a sleeping bag and pad, food, water, changes of clothing and miscellaneous gear. I estimate my pack at around 40-45 lbs. The weight of the packs would take some getting used to and there’d be no high-speed running up and down this trail.

Joanne on Day 1, the John Muir Tail, Yosemite, Sep 18, 1996

JB on Day 1, the John Muir Trail, Yosemite, Sep 18, 1996

The John Muir Trail near the Cathedral Lakes

We encountered a few hikers on that first day, but none were staying at the lakes. By the time we found a good camping spot, set up the tent and began cooking our spaghetti dinner, it was near 5:00PM. Sundown came at 7:30PM, providing time to clean up and store our food. Any edibles that wild critters might seek had to protected. Our technique was to tie them up and hang the bag and bear canister over a tree limb—high enough so that large animals such as bears could not reach them. We never did encounter a bear during this hike, but the threat was always there.

By 8:00PM nightfall had arrived with a dark, steely blue sky and crescent moon. Stars were making their appearance here and there. The temperature had dropped considerably and, since no fires were allowed in this area, it was time to turn-in and test out the sleeping bags. I would find, to my annoyance, that the mummy-style bag I had purchased was not particularly suitable for extreme cold. It was a tad too light and, to make matters worse, the mummy-style did not allow drawing the legs up into a much warmer fetal-style position.

That first night was instructive. The prohibition on fires, the drop in temperature, and only limited battery power for flashlights meant turning in early. If I had a book to read, I couldn’t read it anyway. The extreme cold was evident when I awoke late in the night to take care of nature. As I returned to the tent, I grabbed a water bottle sitting on the ground and put it to my lips for a drink—nothing came out! The water had frozen solid. Never mind; get back in the mummy bag...

The second day took us 5 miles south to the Sunrise High Sierra Camp at 9,400 ft elevation. There we pitched our tent at about 1:00PM, and I took off on my own to explore the local area. Unfortunately, Joanne’s broken ankle had obviously not completely healed. She had been in considerable discomfort all day as we hiked into the higher elevations. At one point the trail reached 9,800 ft. This High Sierra camp is a favorite stopover point along the John Muir Trail—even featuring canvas tents that can be reserved through the Park. On this day, however, the site was completely empty, no tents, no people. I suspect they had already shut down for the season and cleared everything out.

One of the Cathedral Lakes

Echo Peaks, off the John Muir Trail to our left

Cathedral Peak off in the distance

We had our first campfire that night, although firewood in the area was scarce. Another thing that was hard to find was suitable drinking water. Our bottled water had already run out. I had the water purifier pump, but this late in the season running water was hard to find. The pump instructions suggested the best and safest water to filter was water that was moving along in a stream, as opposed to still water in a lake. Eventually, I did find a small stream with maybe an 8-inch wide, 2-inch deep, trickle of water. Nevertheless, I lowered the plastic tubing into the stream and began pumping. Eventually, cool, clear water began filling the bottles. Our water supply was replenished. If a stream was not found or the pump failed to produce, we’d have been in a world of hurt. There are no 7-11’s or camp stores in the wilderness.

My local discovery hike included a visit into a nearby meadow and then a brief climb partway up a granite dome. In the meadow, a herd of deer munched on short grasses and took little notice of my presence. After dinner that evening, Joanne and I sat around the miniscule fire as the night closed in around us. The crescent moon had grown a little larger; the stars were more plentiful. A shooting star even made a brief appearance. We took it as a good sign. Things would be Okay—cold, but Okay.

Time for Plan B

The next morning Joanne and I had a serious discussion about her fitness to continue, specifically how the ankle was holding up. I felt the previous day’s 5-mile trek had taken its toll on her. Throughout that hike, she trailed behind me, trying to hide the discomfort. She never complained, but it was obvious she was laboring. A lot of expense and planning had gone into this adventure—not to mention her flight to the west coast from Maryland. She is a real trooper and did not want to be the one to back down.

But the truth was, we had three more days and many miles of rugged trails ahead of us. Without considerable rest, her condition would only worsen. That’s when I brought out the large-scale geological survey map. We needed the shortest route back to the trailhead and this map showed all the established trails. We would abandon our southerly course on the John Muir Trail and, instead, head west past the Sunrise Lakes, then north to Tenaya Lake. This plan would require a 4-mile hike of ups and downs between 9,400 and 8,200 ft. Joanne will still be hauling her full pack, but we would take as many as rest stops as needed along the way. Tenaya Lake was one of the most popular bodies of water in Yosemite. We’d camp there overnight. The following morning, I would make a solo run/hike from the lake, along the Tioga Road Highway (Cal Rt 120), to retrieve our car at the Cathedral Lakes Trailhead.

And so, that morning of the third day we broke camp and set out for the Sunrise Lakes. Although you’d think the 4-mile distance was but a hop, skip, and a jump—particularly for a pair of runners—Joanne’s ankle pain, the altitude, the rugged up and down terrain, and the weight of our equipment all contributed to a slow, measured pace. We paused a few times for rest breaks and to enjoy the beauty of the environment we passed through. On one occasion we set down the packs and relaxed for several minutes on a sun-warmed boulder. Lunch was in order, so we munched on peanut butter crackers as we took-in the scenery around us: the gray, sloping, rocky ground, the craggy mountain peaks and high buttes. Here and there clumps of mountain pines occupied the lower levels.

On resuming our trek we’d reattach the heavy packs by sitting on the ground with our backs to the pack, placing our arms in the loops and rising with the pack in position. Once beyond Sunrise Lakes we began heading north. Forestry workers were manicuring this part of the trail and other hikers were encountered heading south to Half Dome. That’s Okay, Half Dome wasn’t going anywhere. We’d be back for another try, on another day.

It was about an hour’s hike beyond our lunch break location when I realized my hat was no longer on my head. Since this was my favorite Oriole’s cap, I decided I needed to retrieve it, while Joanne continued to our next rest stop. After depositing the backpack behind a tree some distance away from the trail, I tightened up my hiking shoes and took off running. While there was always a possibility some other hiker would confiscate my cherished souvenir before I got there, that never happened. The cap was there on the boulder, still taking in the view, exactly where I left it. But this little side trip did not stop there. On returning to the wooded area where the heavy backpack was hidden, everything looked the same—the trail, the trees, the underbrush. Exactly where was that pack? Did someone take it? The infamous Sasquatch perhaps?

A hat alone in the wilderness

Joanne sits forlorn at the Tenaya Lake Campground

Tenaya Lake at 8,150 ft elevation

It took half an hour to retrieve the cap and return to the area of the backpack. It was almost another half hour before the pack was found. What looked like an area I would easily recognize, appeared totally different when returning and looking from the opposite direction. A lesson learned. I donned the pack and set off to find Joanne.

We reached the beautiful blue Tenaya Lake by mid-afternoon and set up our tent. Although there were no other occupants there, this was a well-used, formal walk-in campground on the south side of the lake. The lake water was clean and not as cold as I expected. With the sun still high overhead, I decided to strip down to my running shorts and take a dip. I got in as far as my waist, splashed around a bit, and that was enough for me. It was refreshing, nonetheless.

The next morning there was time-enough for a few sips of coffee before heading north paralleling the Tioga Rd. Not much was stirring at 6:45AM; however, it wasn’t long before I met a half dozen-runners preparing for a 13-mile trail run into the Yosemite Valley. In an item for the small-world category, all the runners were strangers to me, but I was surprised to hear they knew two of my fellow Bay-area runners from Alameda.

I arrived at the trailhead shortly after another detour to help a lady in distress. She had lost a hubcap from her vehicle and I paused to help her find it. We never found the hub cap, but she did give me a ride for the remaining 2 miles to the trailhead. The Bonneville started right up and I was on my way.

In a matter of minutes, I was pulling up along the shoulder near the Tenaya campsite. After a small breakfast of dry cereal and coffee, Joanne and I began breaking down the campsite. Our 6-day hike had been reduced to 4 days. We did eventually make it down to Half Dome, but we’d only see it from across the valley. After breaking camp, we drove to Glacier Point—the scenic overlook directly across the valley from Half Dome. The Point provides an iconic view of the granite monolith and much of the Yosemite backcountry. After a late lunch in the valley, our return trip to the San Francisco Bay area was underway. I would make that summit to the top of Half Dome, wearing that same Orioles cap, but it would be a lot more civilized and not occur for another 2 years.

Half Dome as seen from Glacier Point

JB on a hike to the Half Dome summit, Aug 1998

B. Half Dome--Reaching the Summit

Yosemite Valley from the Wawona Tunnel Viewpoint

Every trek worth undertaking has its rewards. These can be the natural beauty encountered, the wildlife you might come across, or the accomplishment of besting a difficult climb over hill and dale. Some hikes will incorporate all of these. Summiting Yosemite National Park’s most famous monolith, Half Dome, is one of these.

Half Dome rises 4,737 feet above the Yosemite Valley floor to a height of 8,842 feet above sea level. There are two primary ways of getting to the summit (1) take the established 8.5-mile overland trail from the trailhead parking lot, approaching Half Dome from the rear; or (2) make a direct assault on the face of Half Dome, climbing 4,737 vertical feet to the top. This option 2, however, is for experienced technical mountaineers using proper equipment and techniques.

Each of the three times I’ve summited Half Dome was via the overland trail. When I first read about Yosemite and Half Dome, a hike to the top was given a prominent place on my bucket list. The first climb was in 1998, followed by climbs in 2006 and 2013 to guide other hiking enthusiasts in experiencing the joy of reaching the top.

Although you may be in a park, hiking Half Dome is no walk-in-the-park. It’s a 17-mile round trip that’s rated very strenuous, requiring a high fitness level. The terrain encountered includes hard rock, packed dirt, loose sand, and the occasional muddy section—all the time moving level and then up, and up. Once beyond the Vernal Falls footbridge there are no more flush toilets and no water fountains. Hikers must plan accordingly, including bringing their own drinking water and food. It will be an average of 10.5 hours before they return to the valley floor.

In the last 900 feet or so the hiker meets a very steep rocky climb, the final 400 feet of which is accomplished with the aid of a pair of steel cables that provide a handhold as the climber makes his way to the top. The two cables are suspended from pipes about 3 feet above the rock face. At approximately 8-foot intervals, at each set of pipes, a 2” x 4” board is laid across the path. These boards provide a more secure landing and resting spot as the climber moves up or down the path. The next board becomes the next objective in an incremental approach to conquering the cable path.

A note of caution. This last 900 feet of trail is fraught with danger and the hiker must traverse this section with care. A fall in this area could be fatal. It’s vital that the hiker wear a suitable pair of gloves that provide a good grip on the cables. Perhaps from carelessness, lack of fitness or from slippery conditions, it’s not unusual for one or two people a year to slip and fall to their deaths in this last 900 feet. I have been lucky that each time I’ve climbed half dome the weather has been warm and sunny. The Half Dome cables are up from Memorial Day to Columbus Day each year.

Once on the summit there’s a feeling of joy and great accomplishment. After the heavy breathing is under control it’s time to explore the area and take in the views. Although it took such an effort to get there, there’s nothing much happening. In 30 to 45 minutes, it’s time to begin the descent to the valley.

The following pix provide glimpses of the climbs in August of 2013, 2006, and 1998:

Half Dome as seen from the Merced River, August 2013

JB and Jane stop for a photo op--the August 2013 hike

The bridge offers a view up to Vernal Falls

The 17-mile r/t hike. Include the yellow Mist Trail on the way up and the blue John Muir Trail on the way down.

JB takes the stone path to Vernal Falls

Jane on the stairs to Vernal Falls

JB surveys the falls

Nevada Falls

Jane is 3 1/2 hours into the hike and just passing through a forested area.

Jane now has a full view of the mountain top. If she looked real close she might see hikers making their way up the final 400 feet to the summit.

We've stopped for lunch before taking on the final section to the top. A local squirrel is interested in any tasty handouts available.

A 10 inch lizared was spotted sunning himself. The big animals such as deer and black bears were probably saving their energies for some nighttime prowling.

Jane makes her way to the beginning of the cable run. She remembered to bring a good pair of gloves for gripping the cables. JB had forgotten about the gloves but a happy hiker just finishing the cable descent donated his to the cause.

Jane begins her 400 foot climb to the top. The boy in the yellow shirt, seeing that Jane was hesitant to begin the climb, encouraged her to go for it. She would not regret it. He was right.

After taking in the awesome views, there wasn't much to do. Some people felt compelled to organize the loose rocks into little towers to the hiking gods.

Time for a rest and to relish our sense of accomplishment at reaching the summit. It's about 1PM and the temperature at the top is in the 90s. Five hours ago we were dressed for 50 degree temperatures. JB has since shed his long sleeve shirt and jacket.

Jane overheard this woman mention she had brought entirely too much water. Since our bottles were completely empty, Jane took some off her hands.

Jane and JB take a photo op. Don't step backwards!

Jane prepares to enter the cable run. The descent is not as strenuous as the climb up, but it is tricky. Carelessness can be painful, if not fatal.

We were half way down the mountain and our water bottles were once again dry. The plan was to sample the Merced River water at this time. Here, JB uses a water purifying kit to pump fresh water from the river. This mountain water was joyously cold and tasty. Some of the best he's ever had.

It's been a long wonderful day! Time for Pizza and beer at the Yosemite Village.

Jane at Glacier Point the following morning. Measuring the last 900 feet of Half Dome across the way.

A telescopic view of the Half Dome summit from Glacier Point. Early morning hikers can already be seen at the top.

A view from Glacier Point of some of the other mountains in the Yosemite back country.

Half Dome Hike in August 2006

Half Dome Hike in August 2006

Half Dome Hike in August 2006

JB takes his grandsons, Nick and Jonathan, on the hike of their lives--reaching the summit of Half Dome. We've stopped for a photo op at the San Pedro Reservoir west of Yosemite National Park.

Half Dome Hike in August 2006

Half Dome Hike in August 2006

We're on a short hike in Yosemite after just arriving. JB points to the sheer face of Half Dome. He sees at least two techincal climbers scaling the cliff face .

The sheer face of Half Dome. Two climbers are taking a short cut to the top.

Two climbers are making their way to the top.

It's the next day and Nick and Jonathan decide to take the more casual , 8.5-mile route to the top.

We're nearing the top of Vernal Falls.

Nick and JB on the trail to Vernal Falls.

We've reached the clearing with a view of the last 900 feet to the summit. The lower curved section is the sub dome. Half Dome rises above it. Climbers can be seen working their way up the cables.

Nick pauses as he makes his way up the many switchbacks in the 500 feet of the sub dome. Some of this so steep a person will resort to crawling along the trail.

Nick is already near the top. Jonathan and JB have yet to begin the cable climb. We've all selected a reasonably good pair of gloves from the pile of used gloves provided for climbers. Jonathan has chosen this moment to inform me he has a fear of heights. That's OK , I will have his back all the way to the top. I urge him along ahead of me.

We've all made it to the summit and we relish the glory of it all.

Nick and Jonathan move ahead of me as we descend the cables to the bottom. Jonathan prepares to go around a climber coming up the cables.

Half Dome Hike in August 1998

Half Dome Hike in August 1998

Half Dome Hike in August 1998

Phyllis enjoys the view at the top of Vernal Falls.

Half Dome Hike in August 1998

Half Dome Hike in August 1998

JB and Phyllis have reached the opening with a view of the sub dome and the Half Dome summit.

JB pauses to take in the view before beginning the ascent of the sub dome and Half Dome.

Phyllis (2nd from left) moves along the switchbacks of the sub dome--making the 500 foot climb to reach the cable run to the summit.

We've made our way up the switchbacks. Now we join those on the 400-foot cable run to the top.

The top of Half Dome in 1998. There's not a cairn in sight!

C. Bryce Canyon National Park

In the latter part of October 2015 JB and Jane packed a lunch and loaded our bags into the SUV for a trip from the San Francisco Bay area into the great American southwest. The goal was to see a little more of this country and to visit a few relatives along the way. JB was two weeks out of thumb surgery, his left forearm in a cast. But there was a pressing need to test some new trail running shoes while the sun was shining and the temperatures were still moderate. The 11-day, 1,500-mile sojourn took us into southern California, Arizona, Utah, back to southern California and finally a return north to the SF Bay area and El Sobrante.

The major hikes on this trip were both in Utah--Bryce Canyon and Zion National Parks.

The first stop in Bryce Canyon was at Farview Point

View from Inspiration Point

View from Inspiration Point

Jane: One small step for women, one giant step…

Navajo Loop and Queen’s Garden Trails, 3.1 miles

Bryce Canyon

Switchbacks down to 5.5 mile Peekaboo Trail

Bryce Canyon hoodoos

Jane on Bryce Canyon Fairyland Loop Trail

Bryce Canyon, JB and a nearby hoodoo

Bryce Canyon, Navajo Loop Trail--and a dog standing

watch

D. Zion National Park

Zion National Park--a view from Observation Point

Zion is about 75 miles southwest of Bryce and is a beautiful counterpoint to to the hiking in Bryce. Whereas Bryce provided great hiking down into valleys and coves, Zion featured many hiking trails that climbed high into the clouds. It was mostly overcast and raining while we were there, but not enough to cancel any hiking.

Jane prepares for the first hike of the day, October 2015.

Jane on 5.4-mile round-trip West Rim trail to Angel’s Landing

JB on trail to Angel’s Landing

Jane near top of Angel’s Landing

Security chains near top of trail to Angel’s Landing. As we eyed the steep drop to the valley below and hung onto the chain for dear life, two young runners came scampering by, not holding on to anything, leaping from rock to rock--the fearlessness of youth.

Angel’s Landing, the last 200 yards. Too dangerous for a one-handed climber.

JB on West Rim trail coming down from Angel’s Landing

The next day: Zion National Park, Virgin River access to River Narrows Trail

JB on the Virgin River near the entrance to the Narrows. There was no hiking the waters of the Narrows on this day for JB and Jane. Threat of flash floods, 12-foot walls of water and death meant we would hike elsewhere.

The switchbacks of Zion’s Observation Point Trail

JB on the 8-mile round trip to Zion's Observation Point

JB on Zion Observation Point Trail

In the clouds at the pinnacle of Observation Point. By the time we reached the top it was noticeably colder and raining.

JB and Jane bundled up against the weather at Observation Point

Looking down at the river and shuttle bus in the valley below

The trail down from Observation Point

The next day: On the road from Utah to southern California